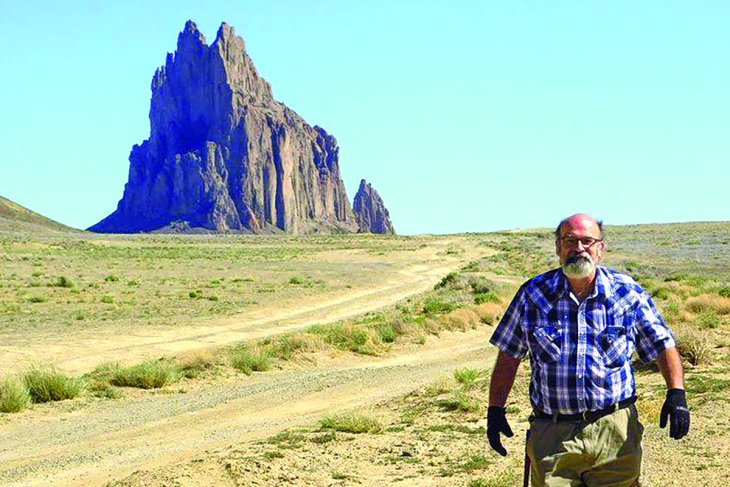

Greg Thompson

"I can just practice dentistry; that’s what I really love and why I’m so happy out here. I don’t have to argue about money, about what insurance will or will not cover. Just sit in my chair and let me take care of you. It’s liberating."

From his home in Tsaile, Arizona, Greg Thompson ’71 gazes over the warm browns and sepias of the Colorado Plateau. Here and there, green trees punctuate the arid beauty. In the distance, the Chuska Mountains graze the sky. “I’m in the most beautiful spot on the Navajo Nation,” he says.

Since 2009, Thompson has worked as sole staff dentist at Tsaile Health Center, one of 11 Navajo Nation clinics managed by Indian Health Service (IHS). Joining IHS was “strictly a financial decision,” he says: His previous 23 years in private practice in Missouri had left him burdened with expenses and constrained by insurance companies’ byzantine patient-classification systems. “I kind of went in blind, hoping things would work out,” he says. He did not foresee the fulfillment the new job would bring. Nor did he fully grasp the challenges facing his patients.

“It’s not uncommon for patients to drive 40 to 50 miles one way to see me,” Thompson says. Spanning portions of Arizona, New Mexico and Utah, the Navajo Nation is the country’s largest Native American reservation, its population of 175,000 spread over 27,000 square miles. Chinle High School buses, serving Tsaile and other Navajo communities, travel more than 6,000 miles daily, often over unpaved roads.

Transportation woes are just one legacy of longtime systemic oppression that’s left almost 36% of Navajo Nation households below the federal poverty threshold. One-third of Thompson’s patients lack running water. One-quarter lack electricity. Diabetes is “rampant,” he says, and healthy grocery stores are scarce (Thompson’s nearest is a two-hour drive away).

Mindful of these hardships, Thompson strives to provide holistic care. “When a 35-year-old male shows up and the last time he was at the physician was for a high school physical, I ask, ‘How long has your blood pressure been high? You don’t know? After we’re done, I’m taking you to the clinic and we’ll make you an appointment.’”

Rural deprivation is not unfamiliar to Thompson, a self-described “Missouri farm boy” whose only indoor plumbing growing up was a kitchen sink. If anything, a bigger shock was landing as a lower at Exeter, after a school superintendent, recognizing Thompson’s intellect, referred him for an interview. “I was exposed to more racial and economic diversity” at Exeter than before, he says. He excelled in science, and after graduating, attended Vanderbilt and the University of Missouri-Kansas City. A summer job in dental research led him to UMKC School of Dentistry, followed by five years practicing dentistry in the U.S. Air Force until he’d earned enough to open his own office.

Unlike private practice, where insurance coverage determines patient population, Thompson’s Tsaile practice is democratic. “I don’t care who you are. … If you show up with a toothache, we’ll treat you,” he says. “I may have a screaming 2-year-old in one chair and an 85-year old grandma in the next.”

He has no plans to retire. “Getting people out of pain is a joy,” he says. “My life is very fulfilling because of the renewed sense of purpose I have, and it’s nice finally to have what I consider some financial security in my life. … I can just practice dentistry; that’s what I really love and why I’m so happy out here. I don’t have to argue about money, about what insurance will or will not cover. Just sit in my chair and let me take care of you. It’s liberating.” After 41 years of dentistry, he’s just getting started.

— Juliet Eastland '86

Editor's note: This article first appeared in the winter 2022 issue of The Exeter Bulletin.