Steffensen graduated from Johns Hopkins University in three years, then joined the U.S. Navy. After emerging from Officer Candidate School, she became an aviation intelligence officer. “I chased Soviet submarines,” she says. She met her husband, also a naval officer, while serving in the military and ultimately left to help raise their three children.

While pregnant with her second child, Steffensen reconnected with the Episcopal Church through talks about faith with a local priest. “My faith came through community involvement,” she says. As the Navy moved them to different locations, she volunteered with her local church and held various positions in church leadership, then pursued a master’s degree in theology at Virginia Theological Seminary.

In the mid-2000s, she embarked on a church mission in Dodoma, Tanzania, teaching theology and biblical studies at Msalato Theological College. It was a trip she was well-prepared for. “[Spending] my Exeter upper year abroad in Barcelona gave me this extreme bravery and an opportunity to meet others who were different from me,” Steffensen says. In Africa, she discovered a love for teaching, as well as a facility for translating theology into a different culture, as she helped train Tanzanian students in Anglican ministry.

Once she returned stateside, Steffensen pursued a second master’s degree in divinity and became ordained a priest in 2012. As assistant to the rector at Grace Episcopal Church in Alexandria, Virginia, she ministered to the church’s Latino congregation, La Gracia, helping them develop their sense of leadership and mission in the parish and wider community.

Once she returned stateside, Steffensen pursued a second master’s degree in divinity and became ordained a priest in 2012. As assistant to the rector at Grace Episcopal Church in Alexandria, Virginia, she ministered to the church’s Latino congregation, La Gracia, helping them develop their sense of leadership and mission in the parish and wider community.

Steffensen’s most recent role drew on her military experience, her commitment to faith and her dedication to serving others. As Episcopal Church canon to the bishop suffragan for armed forces and federal ministries, she provided support to Episcopal chaplains who minister to service members and their families. “It was sometimes difficult work,” she says, noting that military chaplains are under enormous stress, coping with deployments, social upheaval and, more recently, the COVID pandemic. “Mental health issues can affect your work in the military, and I wanted to create a safe space for chaplains.”

Her future plans include returning to Burning Man in 2024. “There’s so much to explore and experience in life,” she says. “Becoming intentionally uncomfortable pushes you into new growth, personally, spiritually and professionally.

– Debbie Kane

This article first appeared in the Winter 2024 issue of The Exeter Bulletin.

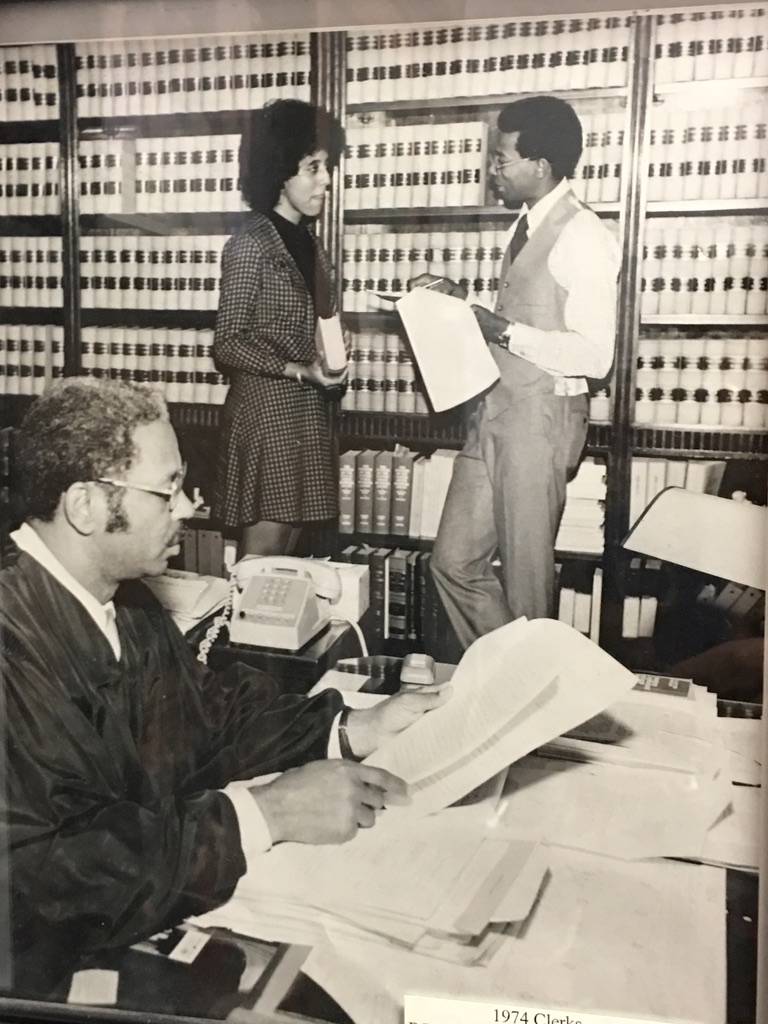

During his senior year in high school, Coleman worked for local civil rights lawyer Julius LeVonne Chambers, who successfully litigated a case forcing the Charlotte public schools to desegregate. “His office and home were bombed,” Coleman says. “To me, that meant he was threatening the status quo, and that being a lawyer was a way to do that.”

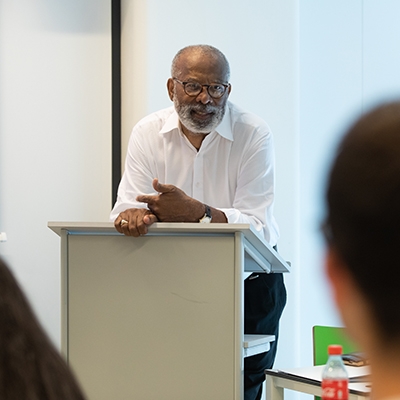

During his senior year in high school, Coleman worked for local civil rights lawyer Julius LeVonne Chambers, who successfully litigated a case forcing the Charlotte public schools to desegregate. “His office and home were bombed,” Coleman says. “To me, that meant he was threatening the status quo, and that being a lawyer was a way to do that.”  In another case with intense media coverage, Coleman chaired an internal committee investigating accusations of rape against several members of the Duke University men’s lacrosse team in 2006. Again, he focused on the need to not rush to judgment. “We wanted to make sure the facts were accurate,” Coleman says. “It’s easy to convict an innocent person, and, in a sexual assault case, it’s particularly hard to prove after a conviction that the perpetrator is innocent.” Charges against the team members were ultimately dropped because of inconsistencies in the accuser’s testimony and ethical violations by the district attorney.

In another case with intense media coverage, Coleman chaired an internal committee investigating accusations of rape against several members of the Duke University men’s lacrosse team in 2006. Again, he focused on the need to not rush to judgment. “We wanted to make sure the facts were accurate,” Coleman says. “It’s easy to convict an innocent person, and, in a sexual assault case, it’s particularly hard to prove after a conviction that the perpetrator is innocent.” Charges against the team members were ultimately dropped because of inconsistencies in the accuser’s testimony and ethical violations by the district attorney.

Once she returned stateside, Steffensen pursued a second master’s degree in divinity and became ordained a priest in 2012. As assistant to the rector at Grace Episcopal Church in Alexandria, Virginia, she ministered to the church’s Latino congregation, La Gracia, helping them develop their sense of leadership and mission in the parish and wider community.

Once she returned stateside, Steffensen pursued a second master’s degree in divinity and became ordained a priest in 2012. As assistant to the rector at Grace Episcopal Church in Alexandria, Virginia, she ministered to the church’s Latino congregation, La Gracia, helping them develop their sense of leadership and mission in the parish and wider community.