Author shares writing insight

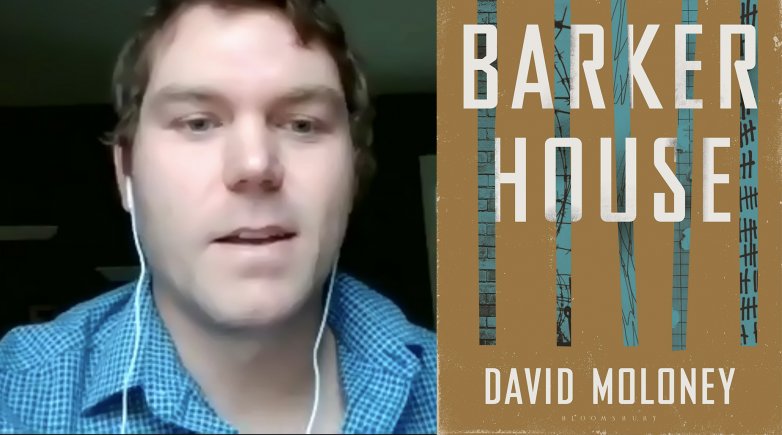

David Moloney addressed assembly virtually and talked about the influences behind his novel Barker House.

In the first assembly of the new year, Exeter welcomed author David Moloney to the virtual stage. Now a lecturer at Southern New Hampshire University, Moloney spent years working as a counselor in the psychiatric ward of a hospital in Tewksbury, Massachusetts and then as a corrections officer at the county jail in Manchester, New Hampshire. In his debut novel, Barker House, Moloney brings forth the complicated and compelling situations, characters and emotions from these experiences.

Moloney explained that his initial instinct was to document his former career in non-fiction, but as he began writing, confidentiality became difficult to overcome.

“Writing fiction was the only way this would have been successful,” he said. “Non-fiction would have really limited what I could have said.”

Moloney's visit Tuesday is part of a parade of authors, poets and journalists who fill the winter term's assembly roster. Last month, J.D. Slajchert '14 shared with his fellow Exonians how his friendship with a terminally ill boy refocused his life and inspired him to write Moonflower, a novel based on his experiences. Sam Wineburg, author of Why Learn History (When It’s Already on Your Phone), spoke about the perils of allowing the internet at our fingertips to confirm our biases instead of more deeply studying the past to cultivate understanding and critical thinking.

Speakers still to come include Sheryl WuDunn, the first Asian-American journalist to win the Pulitzer Prize. Her forthcoming book, Tightrope: Americans Reaching For Hope, co-authored with husband Nicholas Kristof, examines the large swathes of the country feeling left behind by their government and their fellow countrymen. Also ahead: Elizabeth Acevedo, the author of The Poet X, a collection of poems incoming 9th-grade and new 10th-grade students read over the summer and studied during fall term; and Vanessa Friedman '85, the fashion director and chief fashion critic at The New York Times since 2014.

Moloney told his student audience that the “liberation” he found in non-fiction allowed him to create amalgamations of friends and coworkers from his personal and professional life. Moloney called the practice of combining traits from multiple people into one character “Frankensteining” and discussed how to keep those characters from becoming too exaggerated in the process.

“Sometimes we have a lot of great ideas for a character and we can make them so they’re too bloated,” he said. “But a lot of times as human beings we hold two different emotions or two different desires at the same time, we’re almost always conflicted.”

Moloney shared readings from his novel — told as a series of short stories with recurring characters and a linear narrative. One of storylines centers around a female corrections officer. Moderator and English Instructor Matt Miller asked Moloney about writing from the perspective of gender that is not his own.

“I think you can write about the opposite gender — as long as you’re writing it as true as you think it can be,” he said. “If I wrote every character based on me, it’d be a pretty boring book.”

Moloney touched on his experience of promoting his novel during the summer of 2020 and the height of the protests in response to the killing of George Floyd and other Black citizens at the hands of the police.

“When I was doing interviews … every question was about excessive use of force, police brutality or ‘give me the mindset of an officer who does something like this on the streets,” he said. “So, I became a voice for these bad actors because a lot of this book does talk about the abuse of power, because the system allows that abuse of power.”

Moloney talked about wanting to express his personal views on current events during promotional circuit, but wrestled with the prospect of alienating half of his potential audience.

“As an artist and as a writer sometimes you have to decide, ‘Am I going to take a side or stay in the middle?’ — it’s a difficult thing a lot of writers go through.”