The elusive Elizabeth Phillips

History shares few details about the founder's wife, but her contributions to Phillips Exeter Academy are everlasting.

The Academy Center has been renamed for Elizabeth Phillips.

What is there to know about Elizabeth Phillips, the wife of PEA’s founder who has recently been accorded overdue recognition for her role in the origins of the school by becoming the new namesake of our Academy Center?

Sadly, we own only a handful of indisputable facts. She was born Elizabeth Dennett in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, on June 12, 1721; she died in Exeter in 1797. She married Eliphalet Hale, an Exeter physician, in 1736. When she became a widow after 29 years of marriage, she married John Phillips two years later, in 1767. She bore no children.

In 1781, Elizabeth co-signed, with her husband, the famous Deed of Gift, the great founding document of the Academy. Significantly for her, its language included a release of her inheritance (“Likewise Elizabeth, my wife, doth hereby freely and voluntarily relinquish all right of dower and power of thirds in the premises...”). What did this mean? Dower was a wife’s legal right to inherit property from her husband if she survives him (“power of thirds,” similarly, refers to a wife’s automatic entitlement to one-third of her husband’s estate even if he dies without a will).

This was no small legal formality. Mrs. Phillips here voluntarily gave up an important right customarily reserved for women of her time, in order for the new Academy to have the best chance of flourishing after John’s death. Non sibi, in the act of signing her name.

What else do we know about Elizabeth? She was the fourth of seven children born to the Hon. Ephraim Dennett (1683-1741) and his wife Katherine. Ephraim was a prosperous landowner and civil servant in early Portsmouth. (Best fun fact about her father: beginning in 1720, he served for seven years as the city’s coroner — coinciding with the years of Elizabeth’s early childhood.) Her family home (still standing at 73 Prospect St.) was known as “The Beehive,” no doubt because it was a constant hub of human activity. The house was originally built by her paternal grandfather, John Dennett, who had emigrated to New Hampshire from Sussex, England.

What were Elizabeth’s everyday dealings with, and regard for, the Academy that she helped found? Sadly, the surviving documents in the Academy Archives offer only the barest clues. John Phillips’ will of 1789 stipulated that she was to receive only one thousand silver dollars, the household goods which she had brought with her at her marriage, and 50 dollars' worth of produce annually from his farm. Recall, too, that she had waived her dower rights in the Deed of Gift. Given that her late husband’s wealth at the time of his death in 1795 probably made him a multi-millionaire by today’s standards, these provisions for her ongoing sustenance could hardly be called generous.

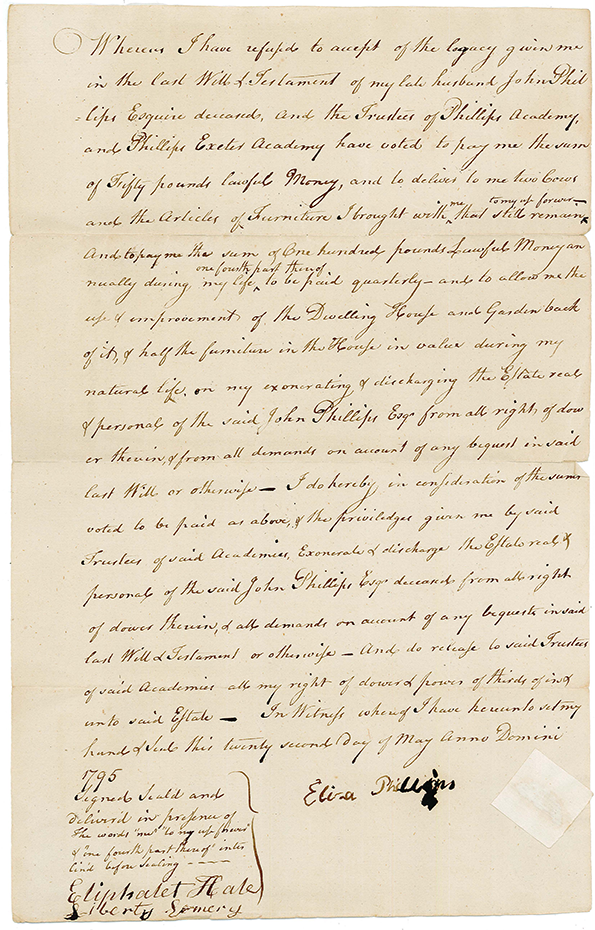

To her credit, Elizabeth, now aged 74, refused the terms of the will and wrote a letter to the Trustees of both Exeter and Andover protesting it. On May 22, 1795, they jointly agreed to better terms for her care.

Exeter’s Trustees proposed to give her 50 pounds, pay her £100 annually, give her a cow, allow her the use of her own house and garden and half the furniture in the house beyond that which was her own property, provided that their Phillips Andover counterparts would cover one-third of all these costs. Andover agreed, and even added another cow. Mrs. Phillips was comfortable with this arrangement until the day of her death, two years later.

Exeter’s Trustees proposed to give her 50 pounds, pay her £100 annually, give her a cow, allow her the use of her own house and garden and half the furniture in the house beyond that which was her own property, provided that their Phillips Andover counterparts would cover one-third of all these costs. Andover agreed, and even added another cow. Mrs. Phillips was comfortable with this arrangement until the day of her death, two years later.

Additional financial documents in the archives show that Elizabeth Phillips played an active role in supporting the Academy. We have, for example, a bill she submitted to the Academy on Nov. 16, 1795, for boarding two students, Horatio Balch and John Thurston, as well as for “entertaining twenty eight persons.”

There is another bill dated Jan. 11, 1797, for dinners and teas she provided for guests.

Her home was something of a “beehive” itself!

Beyond this, Elizabeth Phillips remains archivally elusive. We have no portraiture to show us her appearance — not an oil painting (as one might expect from a relatively well-to-do New England couple), not even a miniature or a silhouette. Did she write letters, keep a diary, stitch a sampler? One searches in vain for such traditional sources documenting an 18th century woman’s lived experience. For now, we have to content ourselves with some legal documents. However, they are more than enough to convince us of her dedication to and sacrifice for the future of this school, Phillips Exeter Academy.