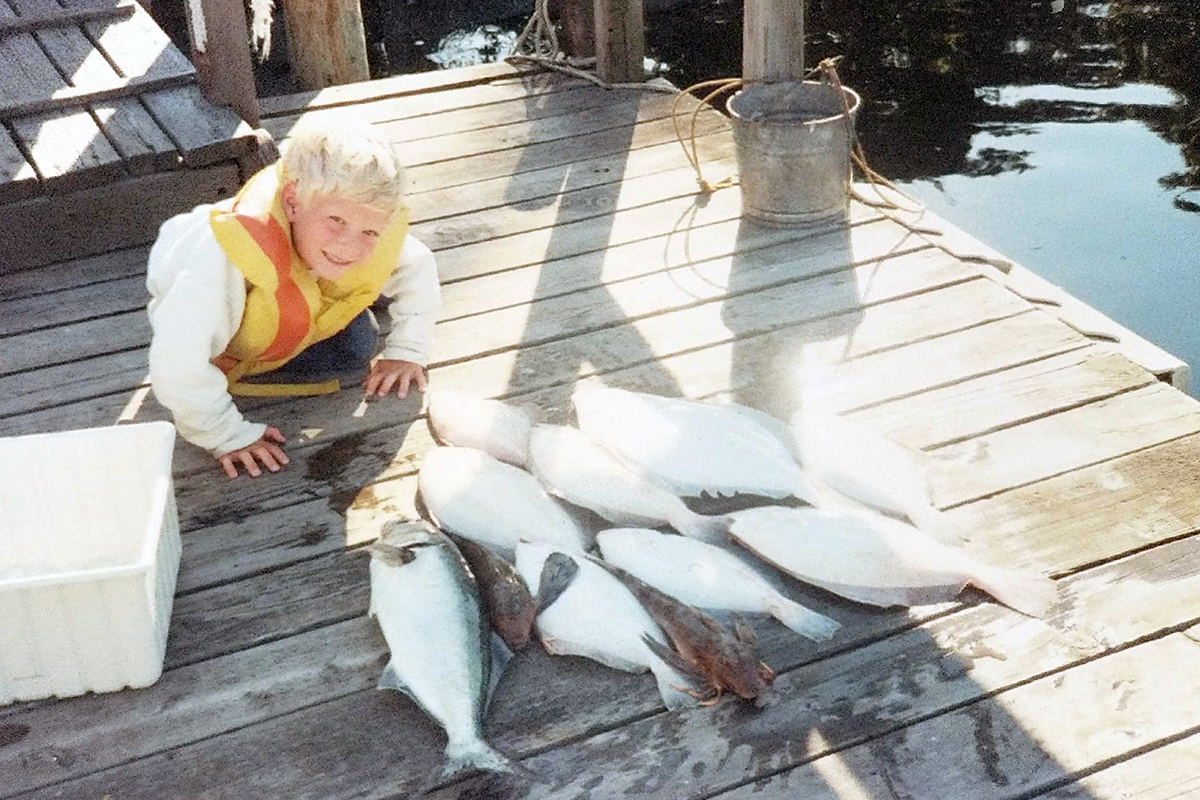

Most days, when the sun rises over New York’s Little Peconic Bay, Peter Stein is at the dock to greet it. From the deck of his 37-foot barge, La Perla, he can look out over the bay’s tidal estuary, fed by inflows from the Atlantic Ocean, and see the links of Shinnecock Hills or the sandy shores of Shelter Island. Stein’s family settled just 20 miles from this spot some 45 years ago. He grew up and learned to fish in these waters. And it’s now where Stein is dropping his lifelines. With no formal training in aquaculture, he purchased acres of muddy bay bottom and opened an oyster farm, naming it Peeko Oysters.

Sounds romantic. But that’s a meme the 37-year-old is quick to dispel. “Most people picture the beautiful bay, the calm water, and think the job is like a Billy Joel song,” he says. “And it’s just not like that.” Stein found out the hard way just how tough farming can be. During his first season in 2016, a nor’easter blew through and Stein’s only boat sank.“ I didn’t prepare correctly,” he says, “which was a little embarrassing.”

Later that year, Stein put hundreds of thousands of baby oysters into the water, secured his gear for the winter and walked away. When he returned in early spring, 90 percent of his oysters and gear were gone. He had used the wrong gear, weighed it down wrong, secured it on the wrong type of line, in the wrong depth of water … and the list goes on. “Mother Nature is going to let you know you screwed up. … She is a relentless and wonderful teacher,” Stein says. After such a devastating setback, many would have given up. Stein rolled with it: “You have to battle back from it and find silver linings and persevere.”

In many ways, oyster farming was an unlikely career choice for Stein. “It’s funny,” he says, “my background is not farming, it’s business development and sales.” After graduating from the University of Pennsylvania with an English degree, Stein spent three years at Accenture doing management consulting. From there, he moved to academics and landed a position teaching sixth grade. After that, he hooked up with the sales divisions of a few startups in the education software technology space. From job to job, nothing really clicked, and eventually fate took over.

When Stein returned from his honeymoon in 2015, his boss greeted him with some bad news — he was laid off. “I was a bit bitter about that,” he says. “But it gave me headspace to just think.” Stein became fascinated with the local-food movement and especially the idea of producing food without chemicals. “I learned about all these cool new things happening in the world of aquaculture and aquaponics and aeroponics,” he says. “And then I started to contact some of the people in my home community to find out if anyone was doing any farming like this, and if so, how I could get involved.”

Stein walked the wharves of eastern Long Island chatting up as many people as he could who were farming in the local waters. “The Harkness table does not necessarily an oyster farmer make,” he says. “But it did teach me to be unabashed about asking elementary questions of any- one who could provide me with sound and wise advice and empirical knowledge that I just simply didn’t have.”

He also reached out to Exeter friends like Sam Bradford ’98, who runs Mac’s Seafood on Cape Cod. Stein shadowed Bradford for the better part of a day to soak up all he could about how to run a successful seafood company. That visit was a turning point. “Sam really gave me the validation and reassurance that what I was venturing into could have some success,” Stein says. “I remember him saying, ‘It won’t be easy, but just go do it.’”

When he met a bayman looking to retire and sell his oyster business, Stein took the bait: “Without hesitation or really any sort of cognizance of what was happening, I said, ‘Yeah, I’m in.’” Now instead of working with people with MBAs and Ph.D.s, he’s hanging with folks who earned their degrees on the water, by his own accounts a “salty” crew.

In 2017, Stein brought just 25,000 oysters to market. This year, he is expecting to bring 250,000. That jump is partially due to the life cycle of an oyster. They take a while to grow. An oyster that is served at a restaurant, for example, is typically 2 to 3 years old. The oysters Stein is putting in the water this year won’t be ready to harvest until 2020.

Stein and his two-man team cultivate, harvest and then deliver oysters to some of the toniest restaurants in New York City, where celebrity chefs such as Tom Colicchio dish them up to well-heeled patrons. Stein also works the private party circuit, bringing his delicacies on the road for special occasions and running oyster-tasting cruises out on the bay. Most recently, he shucked for golfers like Jack Nicklaus at the U.S. Open’s player hospitality tent. But he doesn’t farm oysters just to hobnob with the rich and famous. He’s serious about making a positive impact on the planet. “Even if you despise shellfish as a consumer,” he says, “you should be a big fan of it from a preserve-the-earth perspective.”

A single adult oyster can purify up to 50 gallons of water each day. As the water passes through the bivalve, harmful pollutants are filtered out. Oysters are like vacuum cleaners, mitigating against environmental hazards, Stein says. Aquaculture is also extremely efficient: Farmers produce lots of protein in a small amount of space — all while providing a net benefit to the environment.

“In a small corner of my mind,” Stein says, “I think that the more oysters I grow, the more benefit I am having on our environment and, in particular, the specific estuary in which my farm exists and that I love, and that I grew up in.”

Jim Tselikis, '03 Cousins Maine Lobster

Careers often follow a standard, linear path. An entry-level position leads to a promotion, and so on, in a predictable, forward progression up the corporate ladder. That wasn’t the case for Jim Tselikis. His path was more like a right angle.

The abrupt turn in Tselikis’ professional life occurred in April 2012. He was driving south down the 405 along California’s coast with his cousin Sabin Lomac riding shotgun. They were heading to a nondescript parking lot in Los Angeles — the predetermined site for the grand opening of their fledgling food-truck operation, Cousins Maine Lobster. The idea was to sell the kind of Down East Maine lobster rolls they grew up with to the uninitiated Hollywood set. It was a business plan dreamed up while playing rounds of NHL ’94 on Super Nintendo. “I didn’t expect much of it,” Tselikis remembers. “It was really nothing more than a passion project at the time.” Their entire prelaunch marketing campaign consisted of a single grainy photo posted to Twitter.

Things got real soon after they rolled up to the location. “Before we even opened our windows there were 75 people in line,” Tselikis says. “We had nine people in our food truck, but no one had training, nobody had ever buttered a bun,” he says. “We didn’t even have a cash register. We forgot it.” The motley crew held it together for five hours and the lobster rolls garnered rave reviews. “We closed the window that night and said, for lack of a better phrase, ‘Holy shit, this could be something big.’”

They were right. Within days of opening, the cousins were offered a spot on ABC’s “Shark Tank,” a reality television show where budding entrepreneurs pitch their ideas to established business titans in the hopes of walking away with valuable partners and seed cash. While the opportunity was tempting, the cousins demurred. They wanted to establish their model before trying to sell it on national TV. By October, the cousins had made their 52-minute televised plea and landed a $55,000 investment, plus a partnership deal with real estate mogul Barbara Corcoran. Almost overnight Tselikis was booking spots on mainstream media outlets such as “Good Morning America,” the “Today” show and “Master Chef.” With national exposure, an expanded budget and a new influential partner, Cousins Maine Lobster prospered. Tselikis officially quit his day job of four years as a medical device sales associate at Stryker Orthopaedics, and his career’s right turn was complete.

The company is now valued at $20 million and counts 32 food trucks in 16 cities throughout the country. The owners franchise their business model and have opened six brick- and-mortar restaurants domestically and one in Taiwan.

Through all the changes, the 34-year-old Tselikis has remained grounded by his connection to people. “I always go back to Maine, the industry, our lobstermen, ”he says. “They are the reason we have product. Not a lot of people realize how hard their job is.” The amount of lobster that lands along the coast of Maine each year can vary from 60 million pounds to 130 million pounds, and who gets access to those lobsters is a matter of trust. “It’s not just the one who comes and waves the million-dollar check that people do business with,” Tselikis says. “It’s a relationship built on loyalty, on who you are, who your kids were growing up.”

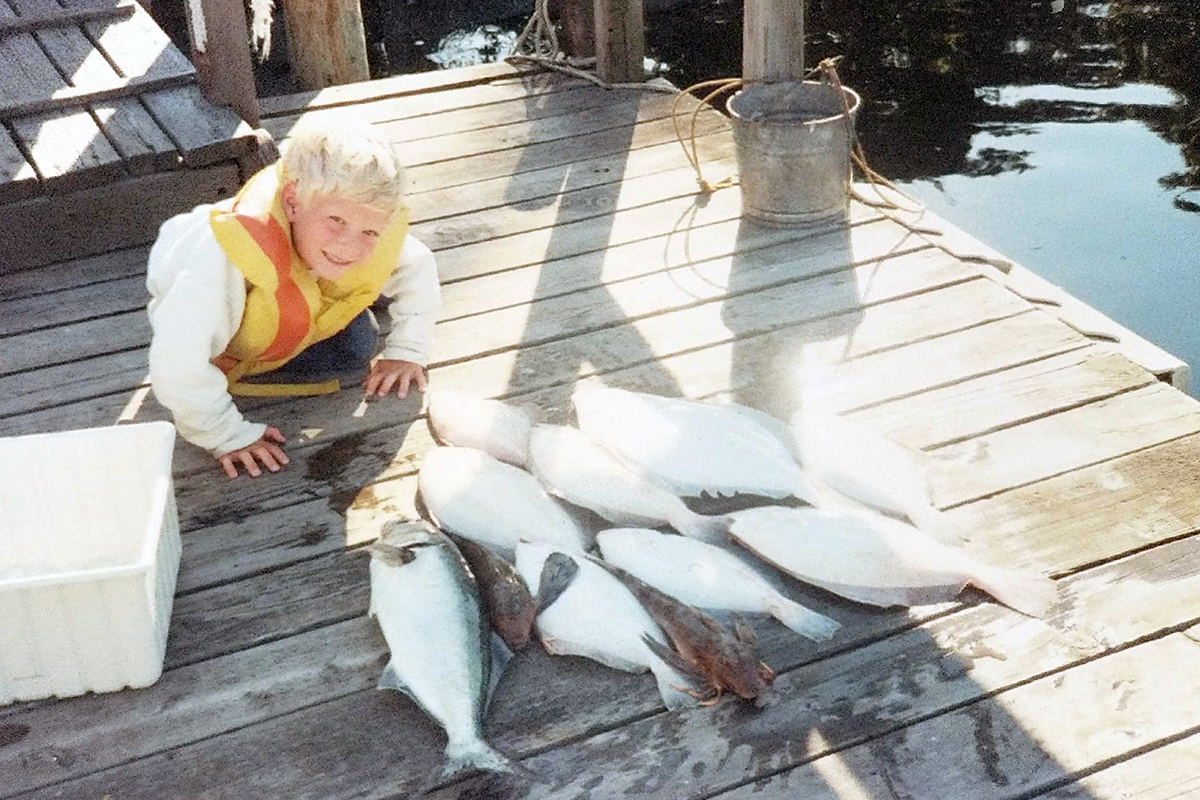

Tselikis grew up in the heart of lobster country, in the coastal town of Cape Elizabeth, Maine. He spent summers working on boats and going to lobster bakes on the beach with family and friends. “It is a different way of life,” Tselikis says. “Down East Maine is very laid back. You take care of people. … There’s an informal love and appreciation for each other.”

Tselikis describes himself as a “fish out of water” when he started as an upper at Exeter. “My town had no diversity and maybe 5,000 people,” he says. “I remember my first math class at Exeter. I was one of three out of 11 kids who were from the United States and I was like, ‘Oh my God, this is cool and different.’”

He spent his first few months focused on academics and the hockey team. When his parents got his first Grill bill for just $1.75, they urged him to “get out more.”

Tselikis signed up for ceramics, joined clubs and began embracing the school’s Harkness philosophy. “At Exeter, I asked a million questions and I never felt bad about doing so because I didn’t want to miss the boat,” he says. He also built lasting relationships with faculty members and especially boys varsity hockey coach Dana Barbin, with whom he still stays in contact. During his two seasons on the ice for Big Red, Tselikis netted 25 goals and 67 assists. Lessons learned at the rink still apply. To this day, Tselikis uses Coach Barbin’s signature quote with his employees: “If you’re prepared, you have nothing to worry about.”

Editor's note: This article first appeared in the summer 2018 issue of The Exeter Bulletin.