At Exeter, I'm one of the co-heads of the Model United Nations club, and by this point in the summer, I'd been meeting with fellow board members and my classmates Stephen McNulty, Alana Yang, Nahla Owens and Phil Horrigan nearly every week to plan for our upcoming fall conference, PEAMUN XII. Each year, our club hosts over 500 delegates on campus from schools across New England for a day of engaging debate. Obviously, this year would have to be different. Over the spring term, we'd tried out several online in-house committees with our club members and were determined to make PEAMUN work virtually. Our staffers were already working on detailed background guides for their committee topics, ranging from “Incarceration During COVID-19” and the “Yemen Crisis” to “The Lion King.”

Thinking of our upcoming conference, I added a short paragraph about PEAMUN to my letter to Ambassador Power before hitting the "send" button. As all of our conference proceeds would be donated to charities and humanitarian organizations, I thought we might have the slightest chance that Ambassador Power would take interest in our event, maybe even agree to make an appearance. But, in all honesty, I expected my email to drift across the vast expanse of the internet into a far-away "junk" folder never to be read.

Some days later, I received a remarkable response. After reviewing her schedule, Ambassador Power agreed to become our keynote speaker for PEAMUN XII Opening Ceremonies, donating her time to speak with nearly 400 students and teachers from schools across Canada, the United States and Mexico. Without compensation, she would join us on a Sunday morning in November to read a short passage from her memoir and engage in a Q&A-style interview with me about her career as a diplomat, journalist and human rights activist.

Our board worked tirelessly through the fall to get ready, answering hundreds of emails; editing endless pages of background guides; prepping for moderating a full day of committee over Zoom; working with Exeter’s IT Director Ms. Archambault on the logistics of our webinar platform; and securing — through the graciousness of the Math Department — classrooms for our 30-person staff to run the conference.

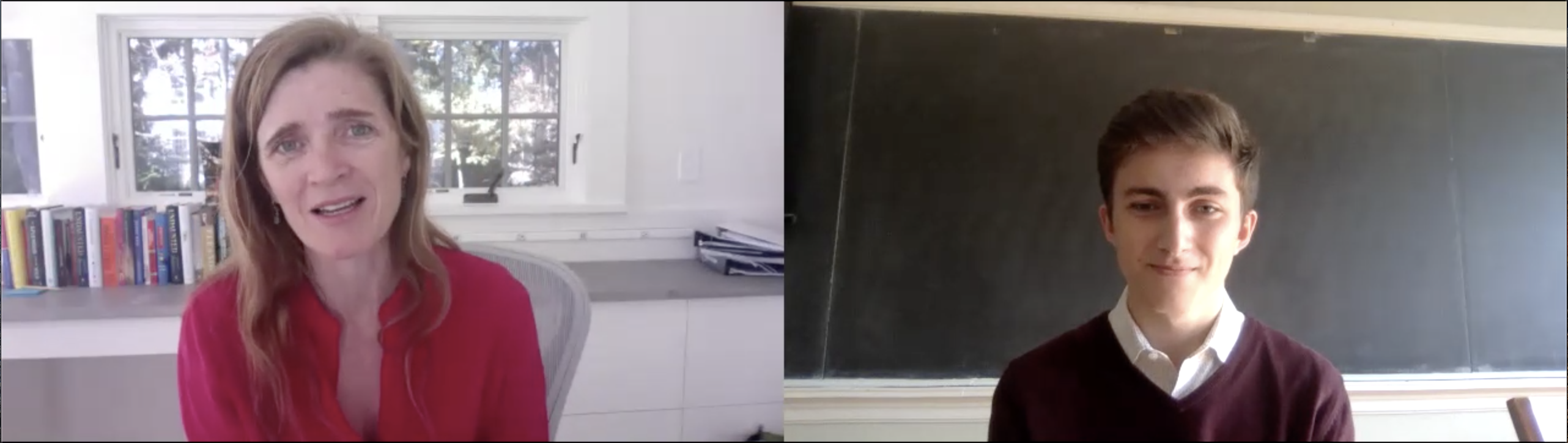

Then came the morning of Nov. 8. As 9 a.m. neared, I sat in the Academy Building, anxious. Just in time, Ambassador Power popped onto the screen and after we quickly exchanged hellos, the webinar went live.

She began with short remarks about polarization in domestic politics before reading a passage from her memoir centered around her relationship with Russian Ambassador Vitaly Churkin. In her time at the U.N., Ambassador Power often publicly criticized Russia's policies as reprehensible, from their involvement in the war in Syria to their stance on LGBTQ+ rights. Yet, throughout her tenure, she still had to work with Ambassador Churkin on countless issues where their interests aligned. She described how close they became, even inviting him to have Thanksgiving with her parents and recommending he watch FX's The Americans (a TV show about Soviet spies in the United States). Ambassador Power's reading offered important lessons about how to coexist and collaborate with those with whom we disagree, an especially important sentiment that morning, less than 24 hours after the U.S. presidential election had been called for Biden.

Following the reading, I began my interview with Ambassador Power, drawing on questions I'd drafted with audience input prior to the conference. Here are excerpts of some of the ambassador’s answers from the Q&A:

On the the role of the United Nations and the United States in upholding human rights:

There is a view out there that America's own record on race, for example, or just given how unequal we are . . . or our record historically in invading Iraq or the Vietnam War or the fact that we provide advanced weapon systems to countries that are involved in wars that are killing a lot of civilians, for example like Saudi Arabia, that all of that should disqualify us on some level from being outspoken on human rights. I think that those mistakes and the human consequences that have resulted absolutely have to inform how America goes about its business in the world, but what you learn when you're in the government is that there's really no such thing as neutrality on human rights.

We're not the world's policemen; we're a catalytic actor on the global stage, and we have a tool kit that involves a lot more than using military force. So, whether it's sanctions, doing what we did with Ebola –– which was deploying our military to build Ebola treatment units, which was a really unconventional use of our logistic capacity — or the kind of aggressive diplomacy we used on Iran and the Paris Climate Agreement, you can see there's a lot of tools in the toolbox that take into account human rights and human consequences.

On the United States’ interventionist tendencies:

I would caution against that word because, is tough, shoe-leather diplomacy to disable Iran's nuclear weapons program interventionism? That's diplomatic intervention in the internal affairs of a sovereign state. So, I would caution against interventionism as a concept because it means very different things to different people. But the use of military force one has to be really, really careful about because it's so unpredictable and we know so little sometimes about the countries in which that is being contemplated. But that's really different than whether you try to pass your policies through a human rights filter and ask yourself: "Do we have tools in the toolbox that might actually help promote human rights or at a minimum, can we take a 'do no harm' stance?"

On American policy regarding refugees and the Trump administration’s decision to set the refugee limit to its lowest point since 1980:

During the Holocaust, we slammed our doors on Jewish refugees who were desperately trying to come to our country. In the last four years, we've slammed our doors on individuals who've fled, for example, the atrocities in Syria and have no place to go, are living in squalor and complete deprivation. Now, there's human rights reasons for being more generous and opening our doors, for sure. A sense that if we didn't know if we were a refugee or an American what would we want the rules to be? How humane would we want our government to be? I think there's good, sound reasoning in terms of finding this moral framework. The other reason is that you don't want millions of people living in squalor and susceptible to radicalization, which has happened so often in refugee camps in the past. So, America should be doing its share and then using that leverage to get other countries to do more . . . so we're not owning the entire problem ourselves.

We then went on to cover a range of topics, with Ambassador Power providing insight into the international response to the Ebola outbreak, as well as reflecting on her career as a war correspondent to stress the importance of "getting close to the people who are at the heart of the issues you care about."

When asked about how she balanced idealism and realism in government, Ambassador Power stated that her role as an activist did not end when she became a government official. She viewed her time in the Obama Administration as "the latest way in which I could try to prosecute my ideals and push for more attention to human rights in our foreign policy, which has neglected it too much."