A living legacy

The engagingly compassionate vision of H. Hamilton Bissell '29 endures today.

“How does Exeter benefit? It has an instruction system which calls for 12 students to be seated around a table with the instructor to talk things over. If all came from the same social and economic strata, their thinking would be almost identical. The scholarship plan gives an economic, geographic and social cross section of the nation and diversified thinking for full discussion of every phase of work in the school.”

—H. Hamilton Bissell to the Miami Daily News, February 15, 1949

Byron Rose ’59 tells the story of his teenage self, “painfully shy” and living in the can’t-get-there-from-here city of Evansville, Indiana, when H. Hamilton Bissell ’29 first came into his life.

Rose had been accepted to Exeter on a generous scholarship but had declined the opportunity. That’s when Bissell turned up to talk some sense into him.

“To get to Evansville by train was not easy, but Hammy came and took me and my father out for breakfast,” notes Rose, who was impressed. “I said to my dad, ‘The worst that can happen is I go there for junior year and come back to Indiana afterward.’”

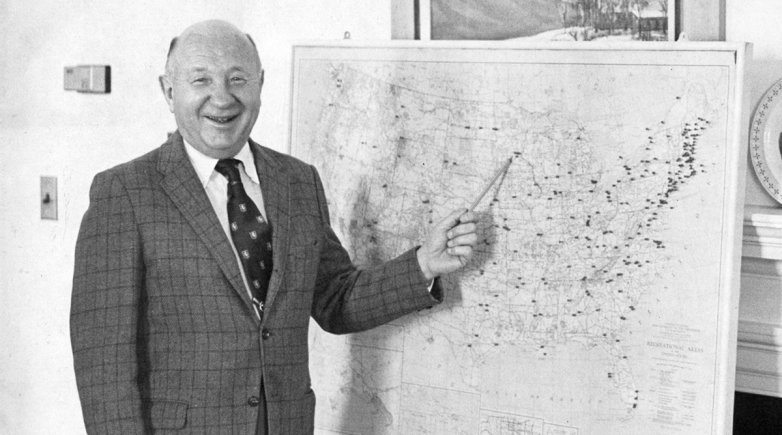

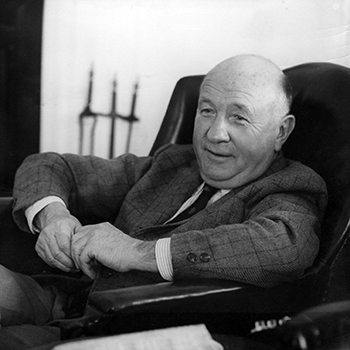

A version of that bacon-and-eggs sales pitch was delivered time and again across the Midwest from 1946 until 1960, with the man simply and affectionately known as “Hammy” making the case to more than 800 young men that Phillips Exeter Academy was the place for them. An English instructor for 13 years before being appointed by the school as its first director of scholarships, Bissell spearheaded an initiative to diversify the Academy’s student body through a comprehensive outreach project. The strategy would enable those boys whose families might not otherwise have the money — or, indeed, even an awareness of the school — to attend Exeter. That proactive effort has had everlasting effects, on the recipients who came to be known collectively as “Hammy’s boys” and on the Academy itself. More than 70 years on, Bissell’s legacy remains vibrant, still full of its original promise.

“I have heard it said that education is America’s magic,” Bissell told Boston Post Magazine in 1949, under the eye-catching headline, “He Scouts for Scholars.” “America is supposed to be a democratic institution. I am sure, however, that economic, religious and racial differences produce attendant inequalities of opportunity among boys and girls.”

In seeking out potential students who were impacted by those limitations, Bissell worked with educational guidance personnel; 4-H, Scout, and Future Farmers leaders; those working with refugees and their families; YMCA officials; and, most famously, newspapermen employing delivery boys.

Rose was delivering newspapers in Evansville when Bissell found him.

“It was purely serendipitous: Mr. Ellis, the man who owned the newspaper, had gone to Exeter,” Rose recalls. “I was a good athlete — I was playing basketball and was a runner — but I was also painfully shy, so I said, ‘No.’ Mr. Ellis said, ‘Well, let’s just send in your application. You might not be good enough.’ Which really spurred me on, actually.”

Rose was accepted on an eye-wateringly good scholarship: “Room, board and tuition was $1,600 for the year; we got financial aid for $1,400, so for $200 my parents wouldn’t have me eating at home,” he laughs. At the time, he says, Exeter’s only publication was a book the size of a novel, with dry descriptions of the school’s courses. But Rose found a magazine article on Exeter that touted a calculus option for uppers. That intrigued the keen math student, but he still wasn’t convinced, and turned down the scholarship. That’s when Bissell showed up for breakfast.

Even after his granddaughter graduated, Bissell continued to attend field hockey team practices. For those young athletes, Nekton observes, having someone with such a deep and enduring connection to Exeter supporting them with such regularity had an indelible impact. “To have an older adult be so faithful was just wonderful for the girls,” she says. “It’s like having your grandpa come out and cheer you on.”

Even after his granddaughter graduated, Bissell continued to attend field hockey team practices. For those young athletes, Nekton observes, having someone with such a deep and enduring connection to Exeter supporting them with such regularity had an indelible impact. “To have an older adult be so faithful was just wonderful for the girls,” she says. “It’s like having your grandpa come out and cheer you on.”