An Oval from a Trapezoid

Edward Harkness made his gift in 130 and changed the whole educational system in our secondary schools.

Teachers share how they shape Harkness in their schools

By Katherine Towler

Illustration by Dave Cutler

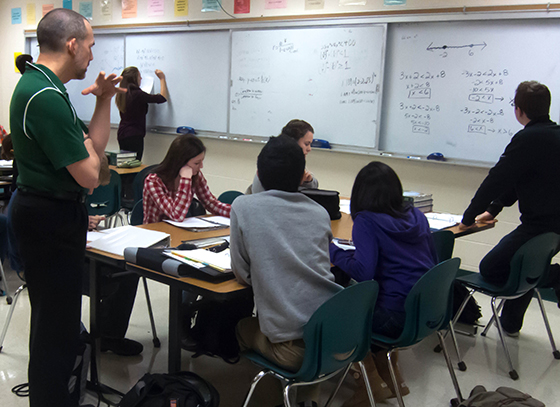

Johnothon Sauer, a mathematics teacher at William Mason High School in Mason, OH, has created a Harkness classroom without a Harkness table. With 25 to 30 students in his public school classes, he wouldn’t be able to find a table large enough, even if a Harkness-style discussion could work with a group this size, which he knows it couldn’t. Despite these less-than-ideal conditions, Sauer has found creative ways to make his classes more student-centered, and to give the kids a much more active role to play in learning math.

Sauer was introduced to the idea of Harkness teaching by his former dissertation director, whose son attended a school that had adopted the Harkness method. She suggested Sauer visit the Academy’s website to learn more. "I had heard of Exeter, but I didn’t know much about the school, and had never heard of the Harkness method," Sauer says. "When I went on the website, it hit me that this was exactly what we were looking for."

Edward Harkness made his groundbreaking gift to Phillips Exeter in 1930 with the aim of changing, in his words, "the whole educational system in our secondary schools. "He wanted to do away with rote teaching and learning, with students sitting in rows listening to an instructor give a lecture. When administrators and teachers at Exeter presented him with a plan that merely tinkered with educational norms without revolutionizing them, he sent them back to the drawing board and urged them to think in terms of small classes and a "conference" approach.

Harkness wanted to see a new way of teaching and learning at Exeter, and he accomplished this, but he had larger aspirations. It was his hope that the innovations introduced around the oval tables at Exeter would spread. Today that hope is being realized, in part, through the seven on-campus summer teacher conferences that Exeter offers to teachers who travel from across the United States and from countries around the globe for professional development.

Last year, 139 independent schools, 70 public schools and 16 countries, including Australia, China, Paraguay and Turkey. Sauer is one of those who has come to Exeter in search of new ideas. He attended the Anja S. Greer Conference on Mathematics, Science and Technology in 2012 and says the experience has transformed both his approach to teaching and the physical layout of his classroom.

When he attended the summer conference at Exeter, Sauer had already begun experimenting with a Harkness approach at William Mason. Now he was able to see the Harkness classroom in action. "It was great to see what a class with a 12-to-1 ratio looked like," he recalls. In his group, led by Exeter Mathematics Instructor Jeff Ibbotson P’17, the conference attendees met around a Harkness table for a class that modeled how instruction occurs at Exeter. "I got a lot out of watching Jeff and how he handled discussion, the questioning techniques he used and the patience he displayed, " Sauer says.

Students in William Mason’s precalculus class meet in groups of eight around each of four islands made from small tables joined together. They work on problem sets and put the results on a whiteboard visible to the entire class while Sauer circulates from group to group. A student in each group is chosen as the scribe for the day. The scribe takes notes and keeps track of who has contributed to the discussion. At the end of class, Sauer snaps a photo of each group’s notes with his tablet.

"Teaching this way is not more work; it’s just very different work, " Sauer says. "I’m still ’on’ all the time, as I am in a lecture format, but instead of delivering prepared material, I’m responding to the way the students are interpreting the material. I get a lot more feedback about individual students and a better feel for where the class is as a whole."

Sauer returned from Exeter with new insights into how to make student-centered classes work in a public school setting with larger numbers. "In my 23 years of teaching, no one had ever discussed teaching this way with me," he adds. "The conference energized me. To see the Harkness method done correctly, and to see that teaching really can happen this way, was the confirmation I needed."#

The Anja S. Greer Conference on Mathematics, Science and Technology has been offered every year since 1985 and is the oldest of the summer conferences. The Exeter Humanities Institute will be in its 15th year this summer, and the Rex A. McGuinn Conference on Shakespeare will be meeting for the eighth year. More recently introduced are the Biology Institute at Exeter, the Writers’ Workshop and the Astronomy Conference. Offered for the first time in 2013, the Exeter Diversity Institute is the newest summer conference.

The conferences run for a week in June. Although many attendees are interested in learning more about the Harkness method, this is a secondary focus for most of the conferences, which emphasize best practices and innovations of various kinds in the different fields. The Humanities Institute is the only conference devoted specifically to implementing a student-centered, discussion-based approach to education. Other conferences, while introducing attendees to the Harkness classroom, provide material on such topics as applications of technology in education and new strategies for teaching writing.

Patricia George, an English teacher at William Mason High School, was inspired by Sauer’s experience at Exeter and attended the Writers’ Workshop in 2013. She hopes to return for the Humanities Institute or the Shakespeare Conference. Although she found the Writers’ Workshop valuable and is a convert to the Harkness concept, George encountered some challenges in applying what she observed at Exeter in her senior English classes. With 30 to 33 students in a class at varying levels, from Advanced Placement track to those with learning disabilities, she has discovered that a completely open-ended discussion does not yield the best results.

"You can’t have a Harkness discussion with 33 students," George says. "But with seven or eight in a group, I found that many of them would hang back and let one student take the lead. I was refereeing too much. So I made the groups smaller and defined the discussion more closely."

George divides her students into eight groups with four in each group and provides them with discussion questions to keep them focused. In the past, she did much more lecturing than she does now, and she is excited about the shift she has seen come about as she has taken on a different role.

"It’s easy for students in a traditional classroom to skate. For me as an instructor that’s frustrating because I want them to engage with the literature,"she notes. "After adopting this approach on a daily basis, I have found that my students are much more able to articulate a thoughtful response to the questions I give them. But I had to feel my way to making this work in a public school with a much bigger class."

.jpg) The summer conferences are designed with high school teachers in mind, but middle school and even elementary teachers have attended and found them beneficial. Katie Leshinsky, a science teacher for seventh- and eighth-graders at Harbor Day School in Corona del Mar, CA, attended the Biology Institute in 2011 while a colleague from her school attended the Mathematics, Science and Technology Conference. On their way to the airport to return home, the two called their school’s principal and asked for Harkness tables.

The summer conferences are designed with high school teachers in mind, but middle school and even elementary teachers have attended and found them beneficial. Katie Leshinsky, a science teacher for seventh- and eighth-graders at Harbor Day School in Corona del Mar, CA, attended the Biology Institute in 2011 while a colleague from her school attended the Mathematics, Science and Technology Conference. On their way to the airport to return home, the two called their school’s principal and asked for Harkness tables.

Leshinsky now has a large, rectangular table in her classroom, which she refers to as a "modified Harkness table." "When you walk into a Harkness classroom at Exeter, no one is hiding," Leshinsky says of the immediate appeal the idea had for her. "Everyone is visible and participating in the discussion. This kind of engagement is especially important at the middle school level."

Harbor Day is an independent school for kindergarten through eighth grade. The middle school classes average 16 students. This has made adopting a more student-centered model easier, although as with any change that asks people to radically shift perspective, it was not without a period of adjustment. Leshinsky explains, "It was a challenge at first getting the students to understand that I wasn’t going to lecture. I wanted to know what they thought. It was a transition to get the students to think differently and to ask questions."

Leshinsky says she has been completely won over despite any growing pains: "I love it. I can’t imagine going back to traditional teaching. We’re around a ’think’ table, not in a sterile classroom. Their neighbors around the table keep the students up to speed. It’s a less intimidating atmosphere. They’re looking at each other, not all staring at the teacher."

With 23 attendees last year, the Biology Institute is one of the smaller conferences. The Mathematics, Science and Technology Conference averages close to 200 participants and the Humanities Institute 70. The size of the Biology Institute was one of the features that made it such a success for Leshinsky. "It’s so small, you become like a little family. You really get to know your peers," she says. "The Exeter conferences are like a think tank. You have teachers who teach a variety of subjects. They share teaching methods, ideas and stories."

Leshinsky returned for the institute in 2012 and ’13, and plans to enroll again this summer. She and her colleague in the Mathematics Department brought their enthusiasm back to Harbor Day, and as a result, all three faculty members in the Language Arts Department attended the Humanities Institute in 2013. Chatom Arkin, who teaches sixth-, seventh- and eighth-graders, was one of them.

Although Harbor Day had already acquired Harkness tables because of that request Leshinsky and her colleague made on the way to the airport, most teachers were not trained in using them. "They were just tables," Arkin says. "Our classes were still very teacher-directed. Now we’re all trained. I was very excited to return to school this year after going to the institute."

Arkin breaks his students into groups of four, as he finds that it is difficult to keep everyone accountable and to give everyone time to contribute in a group of 16. He has also tailored the discussion-based class for middle school students. With seventh-graders, for instance, he will spend one day presenting material and building skills, then the next day asking open-ended questions to generate discussion. "This doesn’t dumb down Harkness at all, but elevates the conversation for middle school students,"he explains. "They have the tools and language for the discussion."

Arkin has signed up to attend the Diversity Institute at Exeter this year and is looking forward to returning: "It’s so great to be in a room with people who are crazy motivated, especially in June.You do feel invigorated."

Many of the teachers who attend the summer conferences note that it’s unusual for them to sign up for a professional development course offered by the same entity more than once. Exeter has become the exception, with many participants returning from one summer to the next. The fact that Exeter offers a variety of topics makes this more attractive, though in some cases teachers attend the same conference multiple times. The Biology Institute, for instance, features a different focus each year so that repeat participants can still benefit from new material.

.jpg) The Ransom Everglades School in Miami, FL, has made the summer conferences the center of its professional development efforts, sending approximately 30 teachers over the past decade. An independent school with 1,066 students in grades 6 through 12, Ransom Everglades has adopted a student-centered approach across the curriculum. John King, director of studies, attended the Humanities Institute in 2004 with three other members of the faculty. "That started it all for us," he says. "We were in."

The Ransom Everglades School in Miami, FL, has made the summer conferences the center of its professional development efforts, sending approximately 30 teachers over the past decade. An independent school with 1,066 students in grades 6 through 12, Ransom Everglades has adopted a student-centered approach across the curriculum. John King, director of studies, attended the Humanities Institute in 2004 with three other members of the faculty. "That started it all for us," he says. "We were in."

Harkness tables would not fit in the classrooms in the school’s humanities building, so Ransom Everglades removed the traditional desks and replaced them with trapezoidal tables that accommodate three students and can be fitted together for a larger group. Classes average 15 to 20 in size, and teachers have the flexibility to arrange students in various configurations for discussion.

King, who teaches history to Upper School students, has six tables in his classroom. Depending on the day and the topic, he may divide students into groups or convene the entire class for a discussion that is largely directed by the students.

The challenge for teachers with this model, King acknowledges, is "relinquishing control." The changes at Ransom Everglades did not happen overnight, but were introduced gradually. A couple of years after King attended the Humanities Institute, the school brought Exeter faculty to Florida to lead mini-institutes for humanities, math and science teachers.

"The math teachers were the most resistant to trying the Exeter approach, so we brought a math teacher down from Exeter," King explains. "Our teachers liked what they saw and one signed up for the math conference the following summer. She returned saying it was the best thing she had ever done."

At first, Ransom Everglades focused only on adopting the new methods in Upper School classes. Over time, however, they saw the benefits this way of teaching might have in the Middle School as well. Now Ransom Everglades sends all newly hired teachers to a summer conference at Exeter, with four teachers attending the Humanities Institute most years.

King says, "There’s a different etiquette about the conversation in our classrooms now. Students have to learn to make room for everyone at the table. Students are less aggressive in their responses in discussion and more inquisitive. They are learning the skill of participating in a conversation with a shared goal."

Other schools have seen similar results and discovered creative ways to "do Harkness." At William Mason in Ohio, for instance, the choir teacher now has students run the sectionals while she rotates from one section of the choir to the next. When students are given more autonomy and control, this school has found, they are more actively engaged in learning.

King concurs: "What has been transformative for us is trying to implement a pedagogy of inquiry. Students drive it instead of everything being driven by the teacher. It was hard for our students at first. They weren’t used to being at the center of the class. But in the last decade, there’s been a clear shift to teachers being more comfortable with letting students steer the ship and students responding well."

Jonothon Sauer sees the summer conferences and the support they have given him as the key to what has happened at his school. "In teaching this way, you’re doing something teachers are not trained to do,"he says. "Attending the conference made me feel I wasn’t out here on an island alone."

Katie Leshinsky agrees, noting, "Usually you might get one or two ideas at a conference. The Exeter conferences have a huge impact. We’re talking about Harkness teaching all the time at our school."

At Harbor Day, as at the other schools, the teachers who have attended the conferences have become ambassadors for the Harkness method, passing on their enthusiasm and ideas to colleagues. Patricia George will be making a presentation at a department meeting at her school this spring and hopes that her demonstration of what she is doing in her classroom will prompt her colleagues to try it.

"We do professional development to make us better at our profession," George says. "What could be better than then turning around and helping to make other teachers better?"

This, it seems, is just what Edward Harkness had in mind. He might not have imagined the diversity of today’s teachers or the variety of what the summer conferences offer, but the way these teachers are helping to spread the message of a Harkness education is surely the realization of his dream.