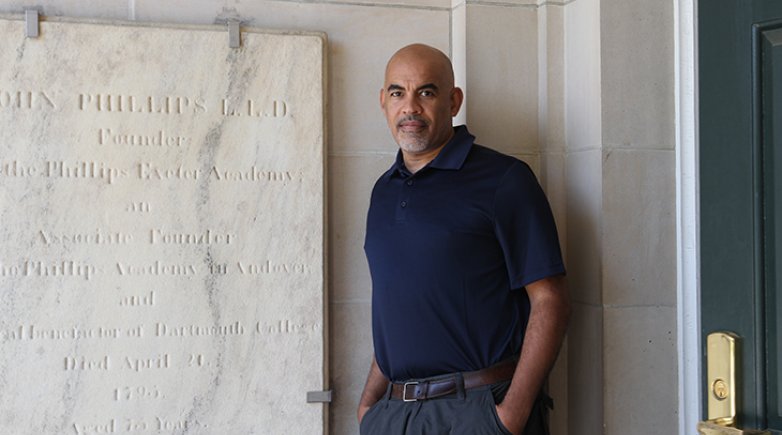

James Meyer '80

"History is not static .. the past isn’t past, it keeps affecting us."

What does it mean to “return”? In James Meyer’s new book, The Art of Return: The Sixties and Contemporary Culture, to return means to revisit a time, a society, or an event that defines and transforms that society. Much more than a mere study of the visual arts of the 1960s, The Art of Return draws on memoir, fiction, literary criticism, philosophy and science. “The book took years to complete,” Meyer ’80 says, “because of the different disciplines involved in its conceptualization.”

Meyer’s wide-ranging volume highlights several historic events — not only in America, but also in select European, Asian and African countries heavily impacted during the ’60s — and their political and essential artistic correlations.

Vietnam and the Kent State student shootings of 1970 figure prominently, as does the Cultural Revolution in China, and other moments of global societal crisis that continue to resonate.

Meyer deftly distills the politics of the time and the art that may have instigated, accompanied or memorialized each of these moments.

Drawing on decades of museum experience — Meyer is currently curator of modern art at Washington’s National Gallery — he offers more than 130 images of works produced by various artistic means during and since the ’60s to explore the ramifications of “return,” and how the process interrogates and differentiates history, memory and nostalgia. While the ’60s have passed, he illustrates how their impact is with us still.

We spoke with him recently to inquire about his book, its Exonian origins and its cultural import.

How did your Exeter experience help to prepare you to write this book — your third and most personal?

My education at Exeter was fundamental to writing this book and to my writing in general. For example, Donald Cole led a course on Chinese history my senior year. I have a chapter called “Red Scarf Children” about Chinese artists and writers born during the period of Mao’s Cultural Revolution, 1966-1976, who experienced that era as children and are now trying to understand it. I conducted research in China and spoke there. I spoke in a place called Tianjin, a large city not far from Beijing. I first learned about Tianjin in Donald Cole’s class. It was one of the cities that was opened up by Western imperial exploration and trading in the 19th century; as he taught us, the attempt to overcome this colonial legacy precipitated the rise of Mao and still impacts China’s interactions with the West.

Did you see yourself moving into the writing life as a student at Exeter?

It was all I hoped. I found my way into writing as an academic and a critic. In the new book, my interest in narrative, in storytelling — how we write the past — has come to the fore. And in a sense it loops back to the kind of expressive and experimental writing I was encouraged to do by David Weber, Robert Grey, Peter Greer, Charles Pratt and Norval Rindfleisch. The book is an attempt to make good on the extraordinary training and encouragement I received in the Exeter English Department.

You’ve stated that this book is “At long last, a work of writing rather than straight art history.” What do you mean by that?

Any work of writing is writing. A seemingly “straight” historical narrative tells a story. In my earlier work, the narrative was diachronic, chronological. I am an omniscient narrator. The “I” is absent. In this book, my experience is central. The opening scene is set in 1971. I am 9 and hitchhiking on Martha’s Vineyard with another boy. We are picked up by a man who looked as if he had stepped out of the cast of Hair. I am old enough to have glimpsed the ’60s without understanding what that meant. The book ends at the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington in 2013. I listen to Myrlie Evers-Williams recall the murder of her husband Medgar a half-century ago. John Lewis describes Bloody Sunday. At that moment we are in the ’60s and in the present, simultaneously. The book tries to capture these returns: my memories and those of more than 20 artists and writers who revisit that time.

The Art of Return utilizes a variety of literary devices to tell its stories. Was it difficult to tie them all together in a cultural history?

It was a great challenge to find a form of writing that could capture what I was after. The focus of my study would not only be visual art, it would include memoir and fiction, literary criticism, philosophy, even science. Entropy, the Second Law of Thermodynamics, is central to my discussion of the Kent State shootings and American decline. I call this the “bad ’60s.” Fiction surfaces in the book where I’m writing about novels that returned to the ’60s and ’70s. Novels like Jennifer Egan’s The Invisible Circus, an outstanding work about nostalgia for that time and the costs of nostalgia; of always wanting to get back to a time that you feel is somehow better than the one you are living in.

The “Long Sixties,” as you call the period from roughly 1955 to 1975, were tumultuous. What turned out to be the most difficult aspect to cover in the book?

There were two particularly difficult parts. Simply trying to define the concept of “’60s return” — my claim that history is not static; that the past isn’t past, it keeps affecting us. Revolutionary eras like the ’60s especially have a longer afterlife. It takes a long time for their impact to be absorbed. The other great challenge was writing scenes including my father, one of which has to do with an argument over a book titled The Greening of America [by Charles Reich, 1970]. It’s a book that supports the counterculture of the ’60s and it inspired an argument at the family table. My father had fought in World War II; he didn’t understand the antiwar movement. He didn’t appreciate the sexual revolution either. His dislike of “the ’60s” made that era fascinating. But writing about my father, who died in 1993, was challenging. Return is an act of salvage: one remembers who and what one has lost.

The Art of Return represents a journey, if not a quest. Have you satisfied your youthful curiosity about a historical moment, glimpsed and missed?

I think I will always continue to be fascinated by that time. But my next exhibition at the National Gallery, on the “Double” in modern art, will go back to 1900 and forward to the present. The ’60s and ’70s will always stay with me, but there are other stories to tell.

— Wes LaFountain '69

Editor's note: This article first appeared in the spring 2020 issue of The Exeter Bulletin.