John Forté

"Music gave me the ability to participate in a way that made me feel so empowered, and like I belonged."

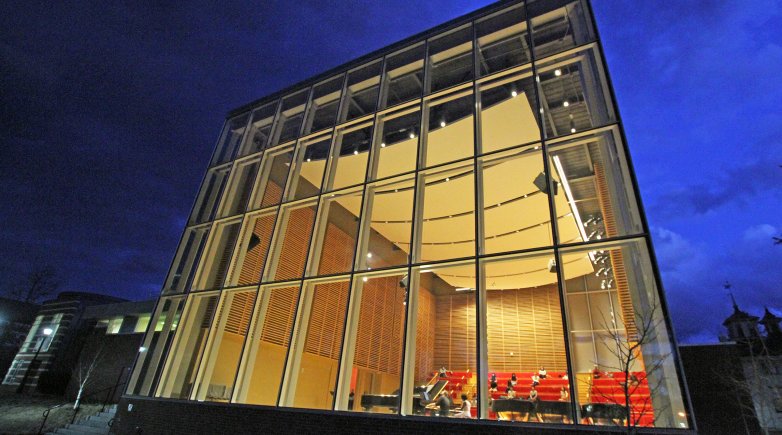

John Forté ’93, a Grammy-nominated recording artist, producer and filmmaker, is asking questions. Seated at a Harkness table in a second-floor classroom in the Forrestal-Bowld Music Center, he wants to know everything about what the eight students in MUS206: Musical Structure and Songwriting are working on. What are the themes, the beats, the styles and the lyrics running through their minds?

“It’s hard for me to hear about songs and music as if it’s not the air that I breathe,” Forté tells the students. “Music is that critical to my existence, and in my life.”

The students begin sharing. Connor Drobny ’24 talks about a linked song cycle he plans to record, as either an EP or an album. “They’re all about the importance of memory, and how memories make up who someone is,” he explains.

Forté lets the silence stretch for a moment as he considers this. “The whole notion of remembering and being reminded — that’s the conversation,” he says.

Raylea Richmond ’26 is writing multiple songs from the perspective of a ghost haunting a particular place and exploring “how [the ghost] sees this space where she’s stuck transformed over time.”

“That’s really interesting,” Forté says. “What keeps us in a place, whether we’re here or not here.” He encourages Richmond to keep exploring the world of the songs she’s writing, and to ponder why that story resonates with her. Moving on to his own music-making process, he starts talking faster, with more emphasis. “Part of me showing up as a creator is explicit,” he says. “I tell myself three things: I’m here, I’m curious and I’m wide awake. Then whatever happens, happens.”

“I took that home and it changed my whole trajectory. Music gave me the ability to participate in a way that made me feel so empowered, and like I belonged.”

“I took that home and it changed my whole trajectory. Music gave me the ability to participate in a way that made me feel so empowered, and like I belonged.”