In the 50 years since he was my teacher at PEA, I’ll bet a month hasn’t passed that I haven’t thought of him.

David Douglas Coffin ’64 (Hon.); P’71

1922-2019

Bradbury Longfellow Cilley Professor of Greek and Chair of the Department of Classical Languages, Emeritus

Bradbury Longfellow Cilley Professor of Greek and Chair of the Department of Classical Languages, Emeritus

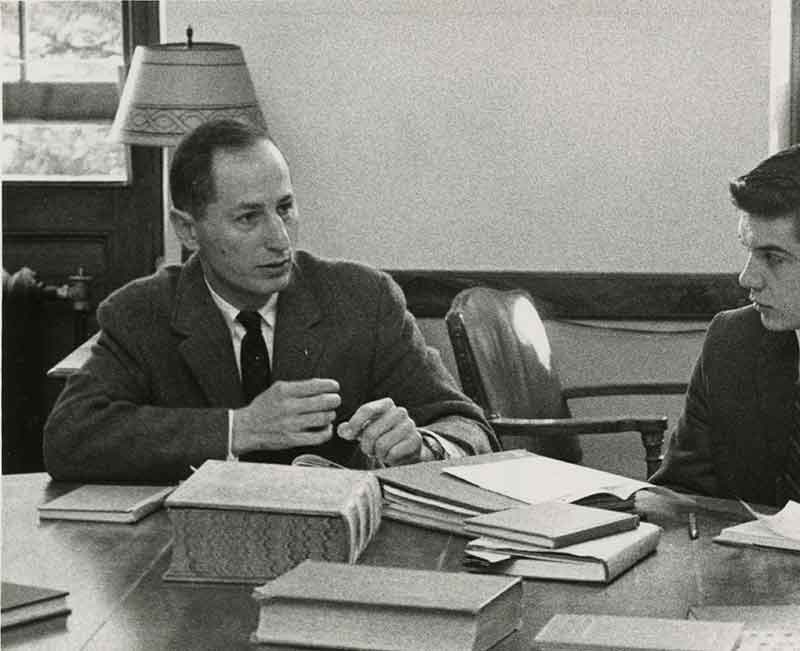

David Douglas Coffin was born in New York City in 1922 and attended Hotchkiss before going on to Yale, where he earned a B.A. in classics in 1942, followed by an M.A. in 1947. Between these degrees, he served as a naval intelligence officer during the Second World War. In 1948, David won a fellowship to study at King’s College, Cambridge, where he met his wife, Rosemary Baldwin. Upon their return to the United States, David and Rosemary settled near Smith College, where David taught classics for three years and where their children, Sarah and Peter, were born. David’s arrival at Exeter in the fall of 1953 marked the beginning of a truly singular career in secondary education. Chair of the Classics Department from 1966 to 1971, he was named Bradbury Longfellow Cilley Professor of Greek in 1969. Adept in Latin as well as Greek, he embraced the department’s traditional emphasis on grammar and precision but combined that with a humanistic sensibility and an appreciation of newly emerging critical approaches to literature. During his tenure, David received distinguished secondary teaching awards from Harvard (1967) and the University of Chicago (1984) — awards that meant more to him than any others, he said, because they had been proposed by former students. In 1986, he received one of the first Brown Family Faculty Awards to be given at Exeter. He retired in 1987.

Outside of the classroom, David served as dorm head in Hoyt and McConnell Halls; coached JV football, club baseball and tennis; and advised The Exonian, the Kirtland Society and the Outing Club. Among myriad other committees, he chaired the NAIS Committee on Latin and the College Board Classics Committee. He created the syllabus for the first Advanced Placement Latin course and co-wrote a guide for aspiring AP instructors.

To this distinguished record of service may be added a further scholarly achievement, one that seems to hail from a mythical age of heroes. In addition to writing a variety of instructional materials that still form part of the department’s curriculum today, David made an enduring impact on Latin instruction across the country with his revision of the land-mark Jenney’s Latin textbook series. For over 30 years, legions of young people made their first acquaintance with the language and literature of ancient Rome through these books — an introduction that few of them realized had been carefully curated and expertly guided by the hand of David Coffin.

In what would have been his seventh year at Exeter, David taught at Eton College in England as part of a Fulbright-funded teacher exchange. He was the first American to teach at Eton in its 519-year history. In a nod to his wide learning, Newsweek observed that “by 5:45

p.m. on his first day, Coffin had lectured on geography, history, English and divinity, as well as classics.” But he displayed more than just knowledge while he was there: After sustaining several cracked ribs playing goalkeeper on the Eton fields, David was heard to say, with no small degree of satisfaction, “They didn’t score a point.” That same indomitable spirit later propelled him to climb all 48 of New Hampshire’s 4,000-foot peaks, along with all the 4,000-footers in the Adirondacks. Eventually coaxed to give up mountain climbing at the age of 80, David continued to play tennis into his 90s.

The reminiscences of his former students are testament to David’s abiding legacy. One alumnus from the ’60s said: “In the 50 years since he was my teacher at PEA, I’ll bet a month hasn’t passed that I haven’t thought of him. I hope he somehow knew how much he did for me.” Few of these recollections proceed very far without mentioning the profound influence of Rosemary Coffin. One measure of the deep impression that David and Rosemary made on the students in their charge is the three funds and fellowships that were established in their names. Active members of the Episcopal Church and engaged citizens in their town, the Coffins were also prime movers in the establishment of the first RiverWoods retirement community, which became a main-stay of the Seacoast region.

But David Coffin’s legacy as a teacher of classics cannot be overstated. One alumna from the ’80s, who had him in just one class, said, “It was, hands down, the most rewarding, engaging, delightful class of my entire high school,

college and grad school career.” An astonishing number of his students went on to become professors of classics at such places as Berkeley, Brown, Chicago, Columbia, Dartmouth, Harvard, Michigan, North Carolina, Princeton and Virginia. In the opinion of one, “I very much doubt whether there is another secondary school — or another individual teacher — that has had so great an effect on a single academic subject.” Was David a demanding teacher? Absolutely. One former pupil, for many years the Anthon Professor of the Latin Language and Literature at Columbia, recalled flunking a test in Coffin’s second-year Latin class; he later remarked that he had been trying to learn Latin properly ever since. David was demanding in the very best way — convincing students that he believed they could succeed and responding with pride and joy when they did. As one student put it, “You cared because you knew he cared.”

In the end, what stands out most is David’s humanity — the momentary retail acts of kindness that make up a day, fill out a week and, eventually, constitute a life. The time he quietly handed a scholarship student new gloves to replace a lost pair. His steadfast, nonjudgmental support of a student in disciplinary trouble. David and Rosemary inviting a student from Thailand into their home every semester to enjoy a Thai meal. His regular attendance at girls field hockey and lacrosse games — no small gesture in the early years of coeducation at Exeter. To those who knew him, David was a man who liked to laugh. Said one alumnus: “I was not a good student at Exeter. As a new lower in 1976, I hadn’t found ‘Easy’ Ed Echols’ Latin 21 all that easy. My prospects were glum for Mr. Coffin’s Latin 22, based on name alone.” But this student persevered, his admira-tion for his new instructor grew, and through some combination of “terror and rapture,” he said, he made it to senior fall, when he found himself in Mr. Coffin’s class again, this time reading Vergil’s Aeneid.

As he remembers it, one day a classmate was practicing his Latin scansion before class with melodramatic passion, falling to his knees like James T. Kirk pleading for the lives of his crew. Little did they know that Mr. Coffin was watching. When they suddenly saw him, they were uncertain how he would respond. They were relieved when he finally reacted with sheer delight. The moment produced an indelible memory for this student, and a wonderful image with which to close this tribute to an educator who made a lifelong impact on so many: “To me, [Mr. Coffin] will always be there, grinning, immortal, at the top of his game.” May we all be so remembered: grinning, immortal and at the top of our game.

The Memorial Minute excerpted here was written by Matthew Hartnett (Bradbury Longfellow Cilley Professor of Greek and chair of the Department of Classical Languages), Beth Nelson Cliff ’77, William T. Loomis ’63, Sarah Pelmas ’81, David Potter ’75 and James Zetzel ’64. The full remarks were presented at a faculty meeting on October 17, 2022.